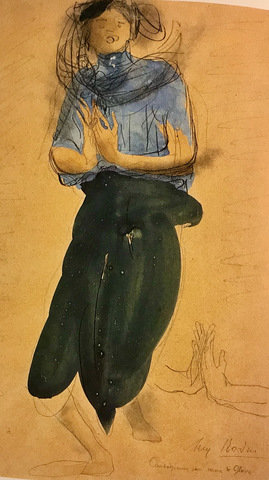

Work on this post has proceeded slowly, but since learning that Auguste Rodin had witnessed Cambodian dancers perform at Marseilles on the occasion of the Colonial Exposition of 1906 in that city, I'd decided to look into it and pick out some threads to follow. I hadn't known that Rodin had been exposed to this deeply affecting cultural tradition; prior to that serendipitous encounter at Marseilles he had no knowledge of it. Moved and inspired, the great artist made a number of pencil sketches of the dancers in situ, applying color afterward. I gather that Rodin made more than 30 drawings of the dancers, along with several portraits of King Sisowath: members of the dance troupe were part of an extensive entourage accompanying the Cambodian king on his official visit to France that year.

Cambodian dance is deeply implicated in the mythology of the Khmer people, as attested by the sculptural friezes adorning the ancient temple walls at Angkor, and on temple sites and artifacts that pre-date the Angkor era. It's been argued that Khmer dancers are associated with fertility rites, perhaps especially in the earlier period (prior to the 6th century of the Common Era). But there is an interesting association as well with the widespread mythic phenomenon of dragon killing (in Khmer culture the dragon is represented by the nāga).

According to Paul Kravath, a scholar of Cambodian dance drama,

At the bottom of the sea a great nāga serpent stretches the entire forty-nine yards of this mythical ocean... Above this, the nāga appears a second time -- a convention suggesting a later action -- supported by two groups of figures. On the left are ninety-two yakkha (ogres) pulling on the head; on the right are eight-eight deva (gods) pulling on the tail. The nāga, the most frequently used oldest Khmer symbol of the earth's forces, is wound around the stone, mountainlike seat of a four-armed deity. The effect of the resultant churning is seen along the top of the carving: thousands of flying dancers emerge from the ocean's foam.

Calvert Watkins has traced a fundamentally significant world myth in his book, How to Kill a Dragon; I wonder whether the Khmer version, with celestial dancers (apsara) and nāga serpent at its core, may correlate with the general framework of the dragon myth, though it seems that Kravath spins the story differently. But my purpose is not to explicate Khmer myth in any detail, but rather tease out some possible implications of Rodin's encounter with Khmer dancers at Marseilles. This will likely entail further consideration of Khmer dance, alongside a glancing look at Japanese Nō theater. Needless to say, the influence of Asian art on Western culture during Rodin's lifetime is large; the subject vast.

A word about my personal involvement with Cambodian dance and dancers. I began working with members of the Khmer community sometime around the year 2000, when I was hired by an arts agency in the Washington, D.C. area to help make meaningful contacts within the diverse cultural communities there. At some point, I wandered into a Cambodian dance practice at one of the local community centers in Northern Virginia, chatted with the parents in attendance that day (the classes were partly intended to introduce young American-born Khmer to essential elements of Khmer culture), and after many more visits I'd established strong relationships with community members, and with the dance instructors – all of the latter widely known within the Khmer diaspora, some whose original training was with the Royal Cambodian Ballet in Phnom Penh, a prestigious company and training center associated with the royal palace. Several of these dancers had defected some years earlier during a performance tour of the USA. I subsequently studied Khmer language at Madison, Wisconsin over two consecutive summers, and have maintained relationships with members of the Khmer community since that time.

Cambodian dance is ritualized and patterned, with gestures, postures, and movements well-established and formalized through the centuries. Dancers convey meaning, emotion, and narrative through facial expression, and through highly stylized gestures and movements -- of the whole body, but perhaps especially by means of the hands and feet. In classical Cambodian dance, the narrative component of the dance has its source in the Reamker, which is regarded by some as the Cambodian version of the Ramayana. While there are significant correspondences between the two, the Khmer version is distinctively Khmer – much as the dance itself is distinctive and independent from classical Indian dance, despite similarities and early scholarship arguing for the derivative nature of the Khmer tradition.

I feel that anyone who encounters Cambodian traditional dance for the first time will be overtaken by the beauty, the intricacy, and the skill of the dancers, and will readily appreciate the challenges they face incarnating the spirit of the characters they portray. The dancers are assisted in this by their traditional costumes, which serve as guideposts to the characters, and perhaps especially by the intricate and beautifully crafted crowns and masks, which are made by one of the master dance instructors in D.C. (who was a prominent member of the dance company at that time).

When considering which direction to take for this post, I wished to understand why Khmer dance may have mattered so much to Rodin at that point in his career (which had been languishing). I don't know that I can provide that understanding here except in a rather perfunctory way. But the Rodin material was suggestive, and I found myself thinking of other cultural traditions, such as Cambodian shadow theater, Japanese Nō theater, and even traditional Hawaiian concepts of cultural knowledge and transmission.

Khmer dance is indeed akin to Cambodian shadow theater – the dancers wear elaborate, highly stylized costumes and crowns (and sometimes, masks too); they move with precision but always according to an established or routinized system; they enact traditional narratives, in many if not all cases based on the Reamker. Perhaps especially, they affect to achieve an otherworldly, suprahuman effect. The shadow theater animators must also dance, as they contrive to make the shadow puppets dance, all action taking place behind the white screen. Both traditions date to the pre-Angkor era; both are sacred to the Khmer people; both are accompanied by the classical pin peat orchestra, consisting of an array of traditional Cambodian instruments. And both are very popular with tourists! According to puppet explicator Kenneth Gross, the shadow animator translates their own "thought, will, gesture, and voice" to the puppets, and these are "made visible the more strongly for his invisibility, showing us gods, demons, ghosts, giants, and warring clans and nobles." Strong magic indeed! And an apt descripton as well of what the living dancers can achieve.

How then does Camdodian dance differ from Cambodian shadow theater? There are many points of convergence, but what are the differences between the two traditions? There are historical explanations for the rise of shadow theater, linked to the fate of the living female dancers at Angkor -- with shadow theater created to provide ritual enactments in their absence. As such the two traditions may be fundamentally the same. In any case, women have played important and varied roles for the Cambodian king. Zhou Daguan, a Chinese merchant who visited Cambodia in 1295 C.E., observing the royal dancers, reported in his Record of Cambodia that,

In the eighth month there is an "ailan", a dance that selected female dancers perform daily in the palace. There are boar fights and elephant fights as well, and again the king invites foreign envoys as spectators. Things go on like this for ten days.

Women might also function as musicians, or as part of the royal guard:

I stayed for a year of so, and saw him [the king] come out four or five times. Each time he came out all his soldiers were gathered in front of him, with people bearing banners, musicians, and drummers following behind him. One contingent was made up of three to five hundred women of the palace. They wore clothes with a floral design and flowers in their coiled-up hair, and carried huge candles, alight even though it was daylight. There were also women of the palace carrying gold and silver utensils from the palace and finely decorated instruments made in exotic and unusual styles, for what purpose I do not know. Palace women carrying lances and shields made up another contingent as the palace guard. Then there were carts drawn by goats, deer, and horses, all of them decorated with gold.

This aspect of women's roles, where they participate in the protection of the king, was attested centuries later, at the time that Rodin observed the Cambodian dancers at Marseilles. During his sojourn in France, King Sisowath was attended by Xavier Paoli, who served as a sort of interlocutor for the king. In his book My Royal Clients, a memoir recounting many years of service to royals from around the world, Paoli focuses attention on perceived gender ambiguity of the dancers:

Sisowath's dancing girls are not exactly pretty, judged by our own standard of feminine beauty. With their hard and close-cropped hair, their figures like those of striplings, their thin, muscular legs like those of young boys, their arms and hands like those of little girls, they seem to belong to no definite sex. They have something of the child about them, something of the young warrior of antiquity and something of the woman. Their usual dress, which is half feminine and half masculine, consisting of the famous sampot worn in creases between their knees and their hips and of a silk shawl confining their shoulders, crossed over the bust and knotted at the loins, tends to heighten this curious impression. But, in the absence of beauty, they possess grace, a supple, captivating, royal grace, which is present in their every attitude and gesture.

To my knowledge the dances were traditionally performed only by females, who played either male or female roles as needed. Over the course of centuries and likely due to historical contingencies, male dancers were integrated into the performances -- though even today women dancers may assume either male or female roles (sometimes depending on availability of male dancers).

I've continually strayed back into a discussion of Cambodian dance, but before closing this post I want to suggest additional connections of possible interest. Having mentioned Japanese Nō and Japanese aesthetics earlier in this post, I want to return to them now, as a means of closing. In his influential essay A Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics, Donald Richie discusses the aesthetic concept of yūgen, which I believe may be relevant to the foregoing discussion of Khmer dance. Richie suggests that,

As a quality yūgen is now mostly associated with the No drama, with a veiled nature seen through an atmosphere of rich if mysterious beauty. Here the yūgen is defined by the dramatist, actor, and aesthetician Zeami Motkiyo (1363-1443) as combining the yūgen of speech, the yūgen of dance, and the yūgen of song. The actor must (in the Rimer and Yamasaki translation) "grasp these various types of yūgen within himself." No matter the character (lord, peasant, angel, demon), "it should seem as though each were holding a branch of flowers in his hand. He should offer this fresh, mysterious reality."

Zeami Motkiyo was perhaps the foremost exponent of Nō theater in Japan; his treatises on Nō are foundational. In "Teachings on Style and the Flower", Zeami employs a version of the Socratic method, casting his lesson as a dialog between master and student:

Question: What is the relation between movement and text in a nō performance"

Answer: That matter can only be grasped through intricate rehearsal. All the various kinds of movement in the nō involved in the performance depend on the text. Such things as bodily posture and carriage follow from this, as well. Specifically, one must project feelings that are in accord with the words being spoken…As the body is used in the service of all that is suggested by the text, these gestures will of their own accord constitute the appropriate acting style. The most important aspect of movement concerns the use of the actor's entire body. The second most important aspect concerns the use of the hands, and the third, the use of the feet. The movements of the body must be planned in accordance with the chant and context expresses in the nō text. It is hard to describe this effect in writing. It is best to observe and learn during actual rehearsals.

When one has practiced thoroughly with respect to the text of a play, then the actor's chant and gesture will partake alike of the same spirit. And indeed, the genuine union of music and movement represents a command by the actor over the most profound principles of the art of the nō. When one speaks of real mastery, it is to this principle that one refers. This is a fundamental point: as music and movement are two differing skills, the artist who can truly fuse them into one shows the greatest, highest talent of all. Such a fusion will constitute a really strong performance.

These comments may apply equally well to Cambodian dance, where there is a shared emphasis with Nō theater on expressive use of the hands and feet, on the close alliance of music with movement, and on the seamlessness between the dancer's body and the performed or enacted text. As with shadow theater, the key element of performance in these traditions hinges on the dancer's (or the actor's) ability to embody character and text, and convey these to the audience. Zeami concludes that,

After all, the actor who has mastered the means to realize his text and to fuse music and movement, he will have learned how to give a strong performance and how to give that performance the quality of Grace as well. He will truly be a masterful performer.

So what does all of this have to do with Auguste Rodin, apart from the transformative experience of witnessing Cambodian dance at Marseille in 1906? In a piece she wrote in connection with a Rodin exhibition at Phnom Penh in 2007, Penny Edwards, a scholar of Cambodia, noted that,

For Rodin, the dancers fused all he admired in classical statuary with the enigma and suppleness of the Far East. They were fragments of Angkor "come to life" - the living incarnation of an apparent contradiction that remained a central preoccupation of his work: that of "motion in stillness." In his artwork, this fascination merged light, fluid strokes in diverse media in a bid to capture light through experimentation with color tints. These features are all hallmarks of the 150 sketches that emerged from Rodin's trip to Marseille.

Indeed, Rodin's biographer Frederic Grunfeld quotes from Rodin's own correspondence to amplify this point:

But after a few days the dancers had to return to Marseille to fulfill the rest of their engagement. "To study them more closely I followed them to Marseille," Rodin told Mario Meunier. "I arrived on a Sunday and went to the Villa des Glycines [to see the dancers]. I wanted to get my impressions on paper, but since all the artists' materials shops were closed I was obliged to go to a grocer and ask him to sell me wrapping paper on which to draw. The paper has since taken on the very beautiful gray tint and pearly quality of antique Japanese silks. I draw them with a pencil in my hand and the paper on my knees, enchanted by the beauty and character of their choric dances. The friezes of Angkor were coming to life before my very eyes... I loved these Cambodian girls so much that I didn't know how to express my gratitude for the royal honor they had shown me in dancing and posing for me. I went to the Nouvelles Galeries to buy a basket of toys for them, and these divine children who dance for the gods hardly knew how to repay me for the happiness I had given them. They even talked about taking me with them."

In his essay, Donald Richie cites Arthur Waley's definition of yūgen, which he says means "what lies beneath the surface", which Richie glosses as "the subtle as opposed to the obvious; the hint, as opposed to the statement." This suggests a connection to a book I've been reading, called Power of the Steel-Tipped Pen, which examines Hawaiian indigenous knowledge as collected and preserved by two native writers in the early decades of the 20th century. Here is a brief passage, first in Hawaiian then in English translation, which briefly addresses the key concept of kaona, which may reflect the Japanese concept of yūgen in conveying the cultural values of "understatement" or "intimation":

O ka olelo Hawaii me ke kaona o kona manao, ka pookela o na olelo i waena o na lahui o ka honua nei, ma na hua mele a na kupuna e ike ia ai ka u'i, ka maikai o ke kaona o ka manao, aole hoi e like me ko keia au e nee nei, he hoopuka maoli mai no i ka manao me ka hoonalonalo ole iho i ke kaona.

The Hawaiian language with the kaona of its meanings is the finest of all languages among the peoples on earth; the beauty and the excellence of the kaona is seen in the song lyrics of its ancestors; not like it is today, where the meaning is just said with no hiding of the kaona.

It strikes me that the dynamic interplay between revealing and concealing, which the Ancient Greeks would define as aletheia, or truth, is a most important function of art -- of art with deep cultural resonance and especially, of art with mythical associations. I'll leave it there for now.